David Collard DPM MHA

Any runner who has been running for any decent amount of time will tell you they have been injured. Small injuries like muscle strains, knee pain, sprained ankles, capsulitis, bursitis, toe and toenail injuries are really common, while some runners may have even suffered large injuries like broken bones from missteps or falls. The list could go on, but we’ll keep this to the point. One injury that is starting to get more attention and research is Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome (CECS), which is a bit of a mouth full and can be debilitating for some athletes, especially runners.

*Note: this is not to be confused with Acute Compartment Syndrome, which is a surgical emergency, usually following severe trauma.

The classic presentation of CECS is often pain that initially begins as a dull ache in the lower leg (although you can also get this in the arms). As runners continue their training regimen, the pain increases to a level that they have to stop. Usually, stopping for a minute or two relieves the symptoms. The onset and degree of the pain can often become very reproducible and runners can almost predict exactly at which mile the symptoms will start.

The pain can be located in different areas of the lower leg (which we’ll define as being anywhere below the knee) or even both legs at the same time. It is usually a full or even cramping feeling in different compartments of the leg (we’ll get to the anatomy in a minute). The pain can also be accompanied by numbness, tingling, or just weakness in the ability to move the foot and ankle. This can even make it feel like the foot has become a numb bag of bones just flapping on the ground with each step.

ANATOMY

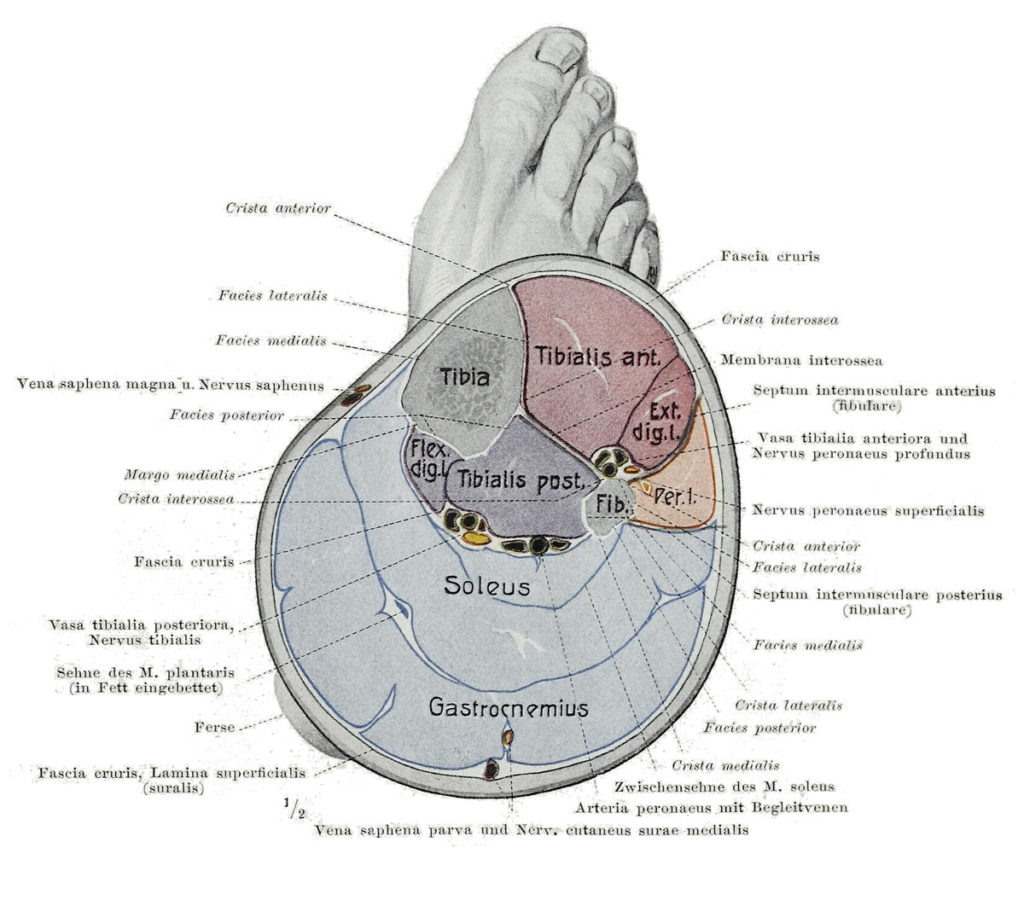

In an overly simplistic view of the anatomy of the lower leg, you can think of it as two long bones (your shin bone–the tibia–and another one you can forget) surrounded by muscles with tendons going down to the foot to make it move in all different directions. All of these muscles are enclosed in wrappers called fascia that hold the bundles together. (Think of it as being like tight cellophane around a few chicken breasts.) In the lower leg, there are four compartments. One in the front, one on the side, and two in the back (one deep and one not as deep).

PHYSIOLOGY

Ok. So everything has its place, and does its job until, well, it doesn’t. That’s when it can go bad.

What exactly is happening with compartment syndrome in runners? We aren’t exactly sure, but we do know some of what is going on. The prevailing idea is that when you exercise, your muscles fill with blood, and when this expands and runs out of room (remember the chicken in the cellophane), it puts pressure on the small arterioles (small arteries) going into the muscle. This causes them to tighten down or even close off, decreasing their nutrient supply. Without oxygen and food, the muscles start “screaming,” and this equals pain. The numbness and tingling may be resultant of pressure on the nerves that run in each of those four compartments. (When you squeeze nerves, they either get numb or start causing pain.) In CECS, it is thought that there is more expansion of the muscles than the fascia wrapper will allow, causing pressure to build to this painful level. Some newer studies not yet published suggest there may be a component of deficiency of one of the major tendons (Tibialis anterior) that could predispose someone to this condition, but this may not account for the whole condition. Research is ongoing.

DIAGNOSIS

The gold standard to get the diagnosis of CECS involves a physician putting tubes into those different compartments and monitoring the pressure both while resting and while exercising. There are other emerging diagnostic imaging studies like MRI and Bone Scans which show promise, but for these, you’d have to rely on radiologists and physicians specialized to recognize the subtle changes that occur with CECS.

TREATMENT

Traditional treatment has been a fasciotomy (essentially cutting that cellophane wrapper). This can be done with large incisions, or with newer techniques that are minimally invasive. These treatments have shown about an 80% success rate. Other non-surgical treatments often tried, but with limited success, include: anti-inflammatory drugs, stretching, prolonged rest, ultrasound, electrical stimulation, orthotics, and massage. But one nonsurgical treatment may have promise.

Image from Wikipedia Commons

Changing Gait

There is research out of West Point that showed significant improvement in patients with CECS who transitioned to a forefoot strike gait. This was a small study, but the participants showed a dramatic decrease in pain and increases in their running distance of over 300%.

The thought is that this improved function lies in the difference in foot and knee position at ground contact. Other research has shown that anterior (front) compartment pressures are significantly influenced by running style — and anterior compartment pressures were significantly increased with a hindfoot-striking gait. So picture a full-knee extension combined with full ankle dorsiflexion (landing with your ankle bent and your foot up) at heel strike. Changing to a forefoot strike, like what is pictured below, may reduce the eccentric activity of the front compartment muscles, thereby reducing the pressure on this compartment.

Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome is a condition not often brought up when talking about running injuries or problems, but might start gaining traction with running clubs. There is well documented evidence of improvement with surgery, but changes in gait may be effective in reducing symptoms without surgery. More research will shed light on the exact processes involved with this condition, and more nonsurgical treatments may possibly emerge.

Schedule or request an appointment with us if you are experiencing symptoms that may be attributed to CECS.